Foster parents describe a system in need of changes

Published 10:27 pm Saturday, January 30, 2016

The state’s foster care system is broken.

Mississippi has pledged to correct what’s gone horribly wrong, but only after a federal lawsuit was filed and the state admitted that it hadn’t complied with the terms of a settlement.

Local foster parents describe a system in desperate need of attention.

“I would like to commend Gov. Phil Bryant and Justice Chandler for recognizing there is a problem and trying to work toward a solution, but I do have questions in regard to who they appoint to some of the commissions and how they plan to fix the system,” said Lenita Watts, a former foster parent who now works in Lincoln County. “The basis for my interview is to make people more aware that there is a major problem, and how we as a community need to fix the local level first. Although it is a state-funded entity, it begins on the local level.”

System changes

Watts said after dealing with multiple county DHS departments and the state department, she saw many aspects of the system that need to be fixed.

“I would say that the biggest change we need is to stop moving children from home to home, unless there is an emergency,” Watts said. “We need to be more compassionate in the nurturing of these children when they are being traumatized from a move to another move, from home to home. We need to make it less stressful, less traumatizing. We need to be more of a caregiver.”

A weak point in the system is the fact that federal and state laws are being overlooked by social workers, judges and guardians ad litem, Watts said.

“Time is of the essence for these children,” she said. “Federal and state laws are in place for children to have a permanent place. The problem is these laws are not implemented through the DHS system and courts in a timely fashion, therefore these children’s lives are in limbo for years.”

Watts said each county system operates differently, and in her experience one county tried to follow the laws and one did not.

“My involvement was with the Jackson County and Lincoln County court systems,” Watts said. “On the one hand, the Jackson County court completely ignored state and federal laws, allowing children to be tossed between different homes without any true supervision or monitoring. Whereas in Lincoln County, Judge Patten strictly followed the mandated legal requirements and appointed a guardian ad litem who actually investigated and put the best interest of the children above some agenda of allowing them to languish in a broken system.”

“Without getting into the details of what our family went through, when we finally were able to present our evidence to the Lincoln County court, the best interest of our children prevailed over DHS and Jackson County politics, or the children just being a number in a broken system,” Watts said.

Watts said she would like to see the system create foster parent support groups, and a private entity that would allow foster parents to express their concerns without fear of the consequences DHS may implement.

In addition, Watts said she would also like to see a CASA, court appointed special advocate, program implemented on a local level. The CASA program takes volunteers and trains them in courtroom procedures, social services, juvenile justice systems and the needs of abused and neglected children, Watts said.

“These volunteers represent the best interest of the child,” Watts said. “They are allowed to do their own investigative work, and present it to the judge. They can agree with DHS or they can disagree with DHS.”

Due to state funding, Mississippi is limited in the number of counties that have a CASA program.

“I believe we are short-handed in personnel and in revenue in the DHS system,” Watts said. “This would be something that would help the Department of Human Services, as well, if each county had their own implemented program of volunteers.”

Former foster parents George and Robyn Linton also believe changes need to be made regarding the treatment of social workers.

“Social workers make squat,” George said. “They’re not compensated for what they have to deal with, whether it be going to gather children in the middle of the night from a drug raid, or going to the hospital to take them away from parents that are strung out. They’re not paid justly for what they do, they are assigned too many cases and many of the recommendations they do make are ignored.”

George said there needs to be more time spent on each individual case.

“Everything is interpreted so generally and so broadly,” George said. “More time needs to be spent on each case, from the social workers to the judge to the Legislature. It needs to be individualized.”

Foster care process

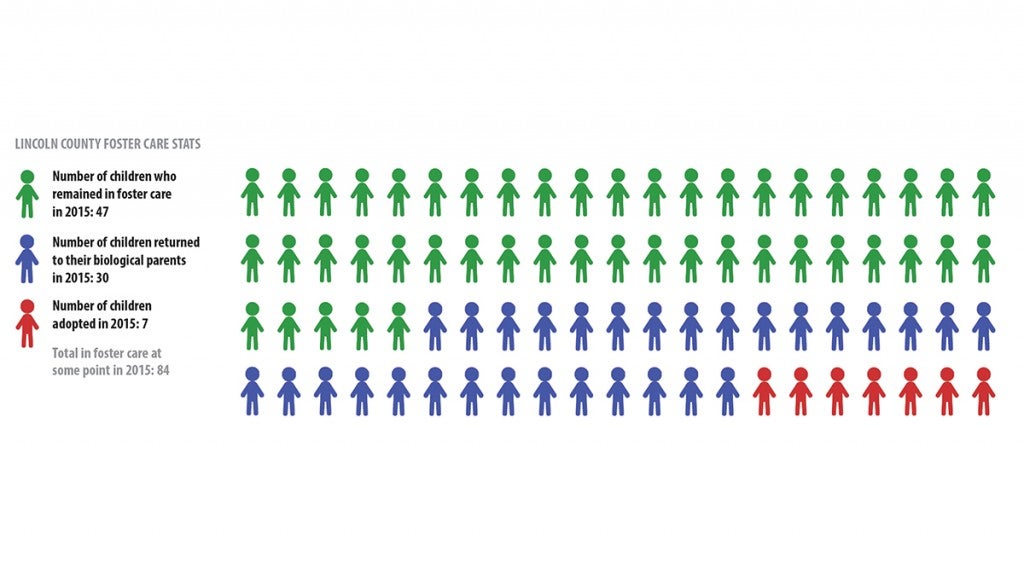

Lincoln County recorded a total of 84 children who were placed in foster care in 2015. The state reported a total of 7,951 children who came through the foster care system last year.

Watts said her and her husband, Doug, received their foster certification through the Natchez Children’s Home when they decided to adopt two children.

“We visited them and felt compelled to try to make a difference in someone else’s life,” Watts said.

The certification process for them was extensive and included CPR and parenting classes, background checks and home study visits.

“My husband and I fostered from 2009 to 2011,” Watts said. “We’re no longer foster parents. You have to keep up your training and your educational certified license. We only fostered the two children and they are the ones we adopted.”

George and Robyn also completed the same tedious certification process to become foster parents.

“There were structured training classes we had to attend, and there was a lot of paper work to fill out,” Robyn said. “At the time our case worker in Lincoln County made the process good.”

“Some of it was a little beyond, but for the most part, the home study was preparing you for something you would do naturally,” George said.

The Lintons served as foster parents to four children, and eventually adopted two of them.

“We knew going into fostering that we wanted to eventually adopt,” Robyn said.

The first set of children we fostered were from north Mississippi, George said. We learned of their situation through my sister and brother-in-law, and that is why we became foster parents, he said.

“The mother of these children left the state with another man,” George said. “And the father was convicted of shaking one of the children’s twin to death.”

Both children had medical issues due to abuse they suffered from the father, George said. The state tried to turn the children over to the grandmother, who did not want anything to do with them, until they made their intentions clear about adoption, he said.

In order to adopt the children, the Lintons had to wait for the state to terminate the mother’s parental rights.

“The problem was, the court could never serve her papers, because they couldn’t find her,” George said. “We went to court four or five times just to have the parental rights terminated.”

If the court tries to serve an individual papers twice and they do not show up to court, the judge is required to run the court order in the local newspaper. If the person does not show up to their court date after the notice is published, then their parental rights are supposed to be terminated, George said.

“The social worker and the judge in north Mississippi were lax,” George said. “They gave the mother twice as much time as they were required to to terminate her rights.”

When the day came for the mother’s right to be terminated, the grandmother stepped in and claimed the children.

“They rushed her through a home study,” Robyn said. “They rushed her through the process that took us almost a year to do. It took her 30 days. I guess it was because she was the grandmother. We never really checked into if that was the standard for a grandparent.”

“They took them away from us the week of Christmas,” George said. “The judge said if we did not cooperate, we would be in contempt of court.”

Adoption process

In 2015, seven children in Lincoln County were adopted. The adoption process in the state of Mississippi is different for everyone and each child, depending on the child’s needs and situation.

“The adoption and foster process with our second set of children went much smoother,” Robyn said. “That was because all of their family gave up rights to them.”

Watts agreed that every child, and every foster and adoption experience is different.

“Our particular situation was very complicated and difficult. There is no cookie cutter explanation to how you adopt because every child has a story,” she said.

Although Watts adopted her children in a different county, she said Lincoln County was involved in certain aspects of the process.

“I did have social workers that visited my home,” Watts said. “I must say my field workers in Lincoln County did a superb job. I have no complaints or anything. I believe Lincoln County has a good support system, as far as the Department of Human Services, but there is always room for improvement.”

‘Reunification’ process

Of the 84 children in the Lincoln County foster care system in 2015, 30 children were returned to their biological parents, with 23 being returned within 12 months of removal from their home, said Cindy Greer, Continuous Quality Improvement director for the Mississippi DHS.

Throughout her experiences, Watts said it is difficult to understand why DHS returns children to situations that are not in the best interest of the child.

“Their policy is — and they will tell you quickly—it’s their policy to reunify children with their biological parents,” Watts said. “I guess my question to the Department of Human Services is, how can you have reunification when you’ve never had unification? DHS is returning children to their parents, even when they miss visits, make promises to the children that they cannot keep and are not following through with what the courts require of them.”

Watts said it is not the state’s job to force parents to be parents and commit to their children.

George said it is political correctness that drives the stigma that every child is better off with blood relatives.

“The main priority is to reunite children with some member of their biological family, but that is not always best for the children,” George said. “Not every case is cut and dry. The general belief that reunification is always the best option is applied to every case, and unfortunately that’s not always true, but is treated as if it is.”

“We know through history though, that it matters not that if the child is born to you biologically or if they’re adopted, the love is the same,” Robyn said. “If you love the child, you love the child.”

As of Jan. 22, 40 children are in the foster care system in Lincoln County and 5,147 statewide.

“I really want to encourage people to become foster parents,” Watts said. “There is a great need out there for homes for neglected and abused children, and I just ask that people think about opening up their homes to give what we are commanded to do under God’s law, and that is to take care of our orphans.”

Visit www.mdhs.state.ms.us for information on how to become a foster parent.

State pledges to make changes

Gov. Phil Bryant appointed State Supreme Court Justice David Chandler as the executive director of Family and Children’s Services last month, and said he hopes to create it as a separate entity from DHS.

“My intent is to improve conditions for children who find themselves in foster care in Mississippi,” Bryant said. “These children must be protected, and that is why I have advocated the creation of a Children’s Cabinet. I’ll be the first to admit that Mississippi can and will do better, and I became personally involved in this issue several months ago. I intend to see this resolved to the benefit of these children and the state.”

“As we all know, the Olivia Y lawsuit has tarnished the image of our state’s treatment of foster children and foster parents, many of whom serve from a sense of caring and Christian compassion,” he said. “As is required by the laws of this state and nation, we must accept our responsibility to adequately care for these children. I will ask your help to support Family and Children’s Services, currently housed in the Department of Human Services, to be fashioned as a separate agency that reports directly to the governor. To reduce the cost, we can utilize that portion of the funding currently being spent at the Department of Human Services for this division, plus an additional amount that must be decided by this Legislature. I am concerned if we cannot make some aggressive commitments to foster care in the state, then the courts will do so for us.”

Bryant and the Division of Family and Children’s Services are currently seeking a budget of $34.5 million from the Legislature for 2016 to help fund additional employee salaries.