Midnight in Bogue Chitto — The shootings that changed the Lincoln County Sheriff’s Office

Published 10:19 pm Friday, May 25, 2018

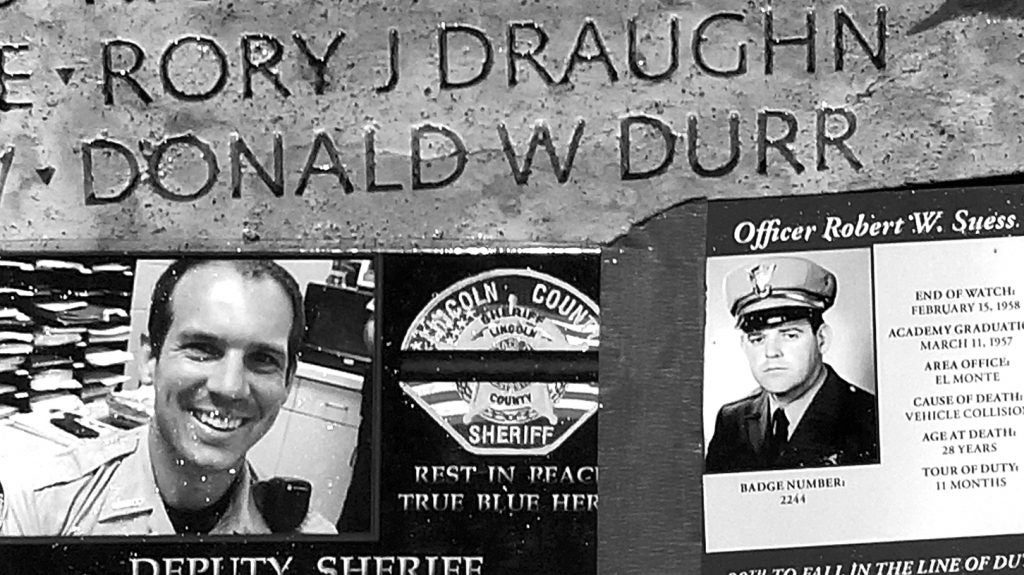

- Photo submitted/Lincoln County deputy sheriff Donald William Durr’s name was added to the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial in Washington, D.C. Over 30,000 people held candles and stood as names of fallen officers were read over the course of half an hour on May 15, during the 37th annual National Peace Officers’ Memorial Service in D.C.

A midnight phone call had never meant so much.

As sheriff of Lincoln County, Steve Rushing’s phone is always ringing, at all hours, for any reason. It had rang in his pocket that afternoon while he fellowshipped at Pleasant Grove Baptist Church’s annual crawfish boil. It rang on the arm of his chair when he came home early that evening to kick up his feet in the recliner. And when its tiny electric lights made the bedroom glow blue in the last few minutes of May 27, 2017, he awoke to the ringing without surprise.

He reached over in darkness, expecting nothing, and answered.

“It was my dispatcher. I could hear chaos in the background, on the radios. She was trying to tell me William was out on a call and wouldn’t answer his radio,” Rushing said. “Somebody else had called in from the scene and said he’d been shot, but we couldn’t verify it.”

No more details. Rushing’s dispatchers know just to give him the gist and get back to the radios — he’ll find out the rest on his own. He rolled out of bed, grabbed his radio and some clothes and took off toward 2871 Lee Drive in Bogue Chitto with hope, but cold in his guts.

“Your first thought is, ‘Aw, he’ll answer in a minute.’ But a little part of you says, ‘something is wrong,’” Rushing said.

As the sheriff drove in the night, the department’s radio net came alive with traffic as every available deputy started toward Bogue Chitto, and the officers at home checked in 10-8 — on duty — and began to assemble. Mississippi Highway Patrolmen and SWAT officers from all around the state started that way, knowing only that shots had been fired, a deputy may have been hit and an armed suspect had hostages inside the scene.

They didn’t know the suspect had gone and Lincoln County Sheriff’s deputy William Durr, 36, was already dead.

According to an FBI summary of the murders, Durr had almost convinced the suspect to leave the home — the call was for a domestic dispute — when the shooter pulled a hidden .40-caliber handgun from his pocket and fired three shots from close range, fatally striking Durr.

Deputy Timothy Kees, a close friend of Durr’s, had just arrived on the scene and heard the shots, but by the time he approached the home the shooter was waiting, now with a 7.62×39 rifle. He fired on Kees, but after Kees sent three rounds back at him, the shooter retreated into the home and killed three more people — 56-year-old Barbara Mitchell; her daughter, 35-year-old Tocarra May; and Mitchell’s sister, Brenda May, 55.

The suspect then fled the Bogue Chitto home on foot, kidnapped Lapeatra Stafford and drove to 1658 Coopertown Road, just off Nola Road, where he released his hostage and killed two children — Brookhaven High School football player Jordan Blackwell and Lipsey Middle Schooler Austin Edwards.

While there, he kidnapped 16-year-old Xavier Lilly and forced the teenager to drive him around for the next four hours. He eventually released Lilly, held up Henry and Alfred Bracy, stole their vehicle and drove to 312 East Lincoln Road. Once there, he shot his way into the home and murdered Ferral and Sheila Burage.

The suspect — Willie Cory Godbolt — was found, unarmed and bleeding from a bullet fired by Ferral Burage, standing on the side of East Lincoln Road at dawn. He is charged with capital murder, murder, kidnapping and burglary, and will face the death penalty. His trial is still in its early phases, with a status hearing set for Aug. 2.

But no one knew all that at midnight in Bogue Chitto.

“When we first got down there it was our understanding the suspect was still in the house,” Rushing said. “It really wasn’t until we got the call about the Coopertown shooting that we learned he wasn’t there.”

When the Coopertown call came in, SWAT officers breached the door and found Durr, Mitchell and the Mays. The sheriff’s office was changed forever.

Rushing said Durr is the only Lincoln County Sheriff’s deputy ever killed in the line of duty. He said losing Durr — a former pastor and youth minister, a man who prayed with suspects and car-wreck victims, a practical joker, a friend to everybody — was a reality check that made him consider retiring from law enforcement.

“I thought about, really, if I wanted to keep doing this line of work. We all went through that,” Rushing said. “But in the end, you don’t just quit. William loved it. That’s what William would want us to do — keep doing what he loved to do.”

There have been no major changes in sheriff’s office policy, or tactics, or equipment in response to Durr’s death. He was outfitted with weapons and armor, communications, all the latest law enforcement tools available to him. Some departments pair officers together, but Lincoln County doesn’t have the manpower, or the budget, to double its daily on-duty roster, Rushing said.

“What’s so different is William did nothing wrong. The guys on shift did nothing wrong. He did his job and handled it like it should have been handled,” he said. “It wasn’t even his call — another officer got the call, but William was closer. That was his nature. He wasn’t one to sit back. He did his job, and he paid the ultimate price for it.”

Rushing said changes to the sheriff’s office have been mental, communal. Support from Lincoln Countians has brought deputies closer to the community, and officers are doing more to support each other, check on each other, he said. The Durr family is part of the department’s family now, and family has become more important.

“It kind of changed our whole outlook on the job,” Rushing said. “You always hear about line-of-duty deaths, but you really don’t see that side of it until it happens. You never think it will happen here, to your guys.”