Laura hits hard and leaves long road to recovery

Published 4:32 pm Tuesday, September 1, 2020

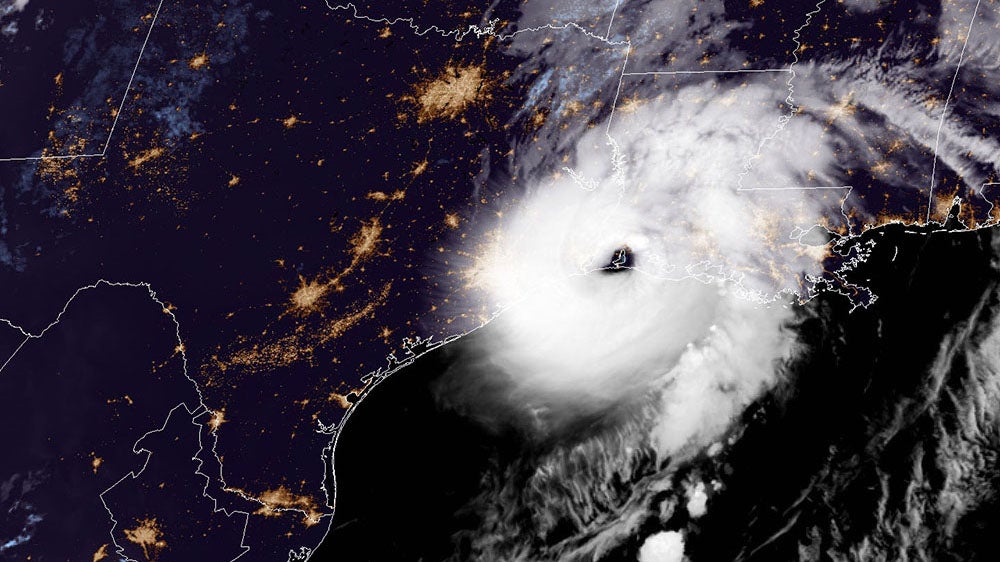

- NOAA satellite image / Hurricane Laura 2020

When Hurricane Laura barreled into the Louisiana coast almost a week ago, Paul Le June was safely tucked away in a Brookhaven hotel. On Wednesday, the Oberlin, La., resident decided to drive his family, two in-laws, and a pet rabbit three hours north in a frantic search for available rooms.

Le June stood in the McDonald’s parking lot the day after Laura left at least 16 dead and more than 700,000 homes and businesses without power. The Louisiana state employee told me he’s a true Cajun who grew up in a household with French as the primary language, but he’s only had to evacuate twice in 15 years. “When we heard it was going to hit as a 4, we had to move. So we called hotel rooms for 45 minutes before we found the two here,” Le June said.

But not everyone in Laura’s path chose to leave. Eighty-year-old Mary Sensat lives in Lake Charles, Louisiana, with her son. He struggles with bipolar disorder and other challenges. “The rest of the family would take me, but not him,” she explained. “So I said, ‘No. I’m staying with him.’”

Riding out Hurricane Laura proved to be scary, though. About 2 o’clock Thursday morning, winds were buffeting Sensat’s house on all sides, exposing part of her roof. As a beam supporting her porch dislodged and blew into the yard, she and her son just crouched in a corner, praying.

“It was the funniest noise, and all these trees popping and the lights and everything,” she recalled. “Then all of a sudden it stopped, and then it whipped up again. The house looked like it wanted to just pop. It would just come out and come back in. We had to nail down one door. My ceilings fell.”

Justin Schroeder spent the night downtown inside his church, First Baptist Lake Charles. Several families huddled together there and prayed as windows blew out and a vacuum-like suction destroyed part of the sanctuary. “I’ve grown up in Louisiana my whole life, but I’d never experienced anything like that intense wind,” he said.

The next morning, Schroeder and his friends went to the third floor of the building and looked out on a changed city. To the west, a battered skyscraper. Beyond that, billowing smoke from a chemical plant fire. And downed utility poles and trees had made many streets and even parts of Interstate 10 impassable.

That’s why convoys of relief workers Thursday morning detoured on rural blacktopped roads, passing through towns like Kinder, where insulation from the roofless Super 8 caused “snow” to cover the parking lot, and Lawtell, with its flooded streets. Along the way they saw acres and acres of sugarcane laid low. Wayne Collins described the crop in Port Allen: “Right now it’s flat. It’s laid flat over. As the sun shines on it, the tops are going to turn and go up toward the sun. So, it’s going to be like an “s.” It’s going to be crooked. But machinery has advanced to the point where they can pick it up and harvest it without it being a total loss. They will lose some though.”

The first Samaritan’s Purse truck pulled into downtown Lake Charles Thursday afternoon. Todd Taylor is leading the response team, and he said their main focus is helping people get back into their homes. Volunteers will cut trees, clear yards, tarp roofs and remove wet sheetrock. With temperatures nearing 90 in Lake Charles this week, it’s hot, dirty work.

“It’s going to be weeks before some people get electric restored, and several of the local water systems are down,” Taylor said. “That’s going to be a big issue slowing people’s return. They can’t return home until they can flush commodes and get running water.”

And then there’s the extra layer of COVID-19 complications. Taylor says Samaritan’s Purse has a pool of 150-thousand volunteers from Seattle to Florida and all points in between. But those wanting to help in this disaster face a new requirement.

“If volunteers choose to go out with us and house with us, they have to come in with a negative COVID test in hand. It can’t be more than 72 hours old.”

Kim Henderson is a freelance writer. Contact her at kimhenderson319@gmail.com. Follow her on twitter at @kimhenderson319.