Infrastructure bill to bring billions to MS for roads, bridges

Published 1:00 pm Wednesday, November 17, 2021

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act is set to invest $1 trillion into the United State’s failing infrastructure. The largest federal infrastructure investment in more than a decade, it could go a long way toward relieving the financial strain on drivers.

A recent study published by QuoteWizard ranked states by worst road infrastructure. Mississippi is No. 2 on the list.

The study found nearly 20% of the nation’s roads and 6% of bridges are currently in unacceptable condition, according to the Federal Highway Administration standards. Aging roadways cost drivers an average of $555.66 annually in repairs. Mississippi’s average cost is $820.

States were ranked based on percentage of non-acceptable roads and square mileage of poor bridge decks, compiled from FHA and Bureau of Transportation Statistics data.

Worst on the list was Rhode Island, with 50% of roads non-acceptable and 23% of bridge decks ranked “poor.” The average cost per motorist for annual repairs was $823.

Though Mississippi drivers spend nearly the same amount annually, the percentages of non-acceptable roads and poor bridge decks are much lower — 27% for roads and 4% for bridges.

The states with the highest per-driver cost were Oklahoma — $900 — with 7% of roads and 5% of bridges unacceptable/poor; and California — $862 — with 34% of roads and 10% of bridges unacceptable/poor.

Wyoming did not have the lowest cost per driver, but it did top the list, with 5% of roads and 7% of bridges unacceptable, and a cost of $356 per driver. Tennessee also had only 5% of roads unacceptable, and Idaho had 4%. Georgia, Alabama, Florida and Hawaii had only 2% poor bridges, and four states ranked 1% — Nevada, Utah, Arizona and Texas.

The study found a direct correlation between states that use funds to maintain roads and states that rank well in overall road infrastructure. Meanwhile, states with poor road infrastructure had higher costs per driver and worse road conditions across the board. States spending the least on road repair were Rhode Island (2%), Illinois (4%), Ohio (4%) and Mississippi (4%).

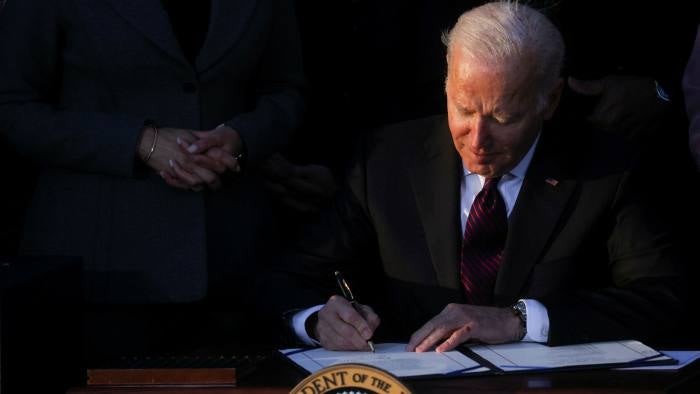

Infrastructure repair has been shown to not only keep motorists’ costs down but as an important tool in job creation. According to The Brookings Institution, a national non-profit public policy research organization, 13,000 jobs are created for every $1 billion spent on highway infrastructure. President Joe Biden says his plan will create 1.5 million jobs per year for the next 10 years.

“It will create millions of new jobs. It will grow the economy, and we’ll win the world economic competition that we’re engaged in in the second quarter of the 21st century with China and many other countries around the world,” Biden said.

Sen. Roger Wicker, R-Miss., Monday afternoon released the following statement on the signing of the act: “Roads, bridges, broadband, ports, rail and clean water are the building blocks of a healthy economy. This legislation focuses on those core priorities, and I am happy to see it finally signed into law. Mississippi will soon see major investments in our state’s hard infrastructure, including $3.3 billion for roads and highways, $225 million for bridge replacement and repairs, a minimum of $100 million for broadband infrastructure, $283 million for water infrastructure, and significant funding for Army Corps of Engineers projects and port and rail improvements.”

The $1 trillion dollar plan is split into six main areas:

• $550 billion in new funding for transportation and utilities

• $110 billion in roads, bridges and major projects

• $66 billion toward passenger and freight rail

• $65 billion to expand broadband access

• $55 billion to improve water utilities and replace lead pipes

• $39 billion for public transit

Biden instructed his Cabinet on Friday to rigorously police the coming investments in roads, bridges, water systems, broadband, ports, electric vehicles and the power grid to ensure they pay off.

In order to achieve a bipartisan deal, Biden had to cut back his initial proposal of $2.3 trillion by more than half. The bill that became law Monday in reality includes about $550 billion in new spending over a decade, since some of the expenditures in the package were already planned.

Historians, economists and engineers stressed that $1 trillion was not nearly enough to overcome the government’s failure for decades to maintain and upgrade the country’s infrastructure.

“We’ve got to be sober here about what our infrastructure gap is in terms of a level of investment and go into this eyes wide open, that this is not going to solve our infrastructure problems across the nation,” said David Van Slyke, dean of the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University.

“Yes, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act is a big deal,” said Peter Norton, a history professor in the University of Virginia’s engineering department. “But the bill is not transformational, because most of it is more of the same.”

Norton compared the limited action on climate change to the start of World War II, when Roosevelt and Congress reoriented the entire U.S. economy after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Within two months, there was a ban on auto production. Dealerships had no new cars to sell for four years as factories focused on weapons and war materiel. To conserve fuel consumption, a national speed limit of 35 mph was introduced.

“The emergency we face today warrants a comparable emergency response,” Norton said.

Yale University economist Ray Fair studied the size of the U.S. infrastructure gap in a September research paper. He found a sharp decline in infrastructure investment as a percent of the overall U.S. economy starting in 1970, a trend shared by no other country, though some nations did begin to invest less in infrastructure somewhat later.

When Fair looked at Biden’s infrastructure bill, he examined the size of the shortfall if infrastructure investments had continued at the 1970 pace. He found that Biden’s spending covered about 10% of a $5.2 trillion gap.

“The bottom line is that the current infrastructure bill is quite modest,” Fair said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.