The other William Durr — A fallen hero, and much, much more

Published 10:30 pm Friday, May 25, 2018

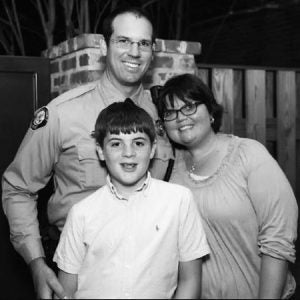

- Above: A line of wooden crosses stands on the side on Hwy. 51 near Bogue Chitto Road in honor of the men and women killed Memorial Day weekend 2017. Below, left: Sheriff’s deputy William Durr, and Durr with his wife Tressie and son Nash; Below, right, in descending order: Austin Edwards, Jordan Blackwell, Sheila and Ferral Burage, Barbara Mitchell, Brenda May and Tocarra May.

She has reminders. All of them. Locked away in a room at home, protected, Tressie Hall Durr has saved it all, every piece.

She has flags of red and white, and blue and black. She has memorial plaques of stained wood and polished brass. She has the hand-written poems and homemade art placed on his Charger when it was parked outside the courthouse as a tribute and covered, by the community, in flowers. She has his boots.

A year after her husband, Lincoln County Sheriff’s deputy William Durr, was killed in the line of duty, she paints the thin blue line on her toenails and wears a bracelet that says, “I love you, William,” in his handwriting. She keeps his memory warm, cries when she hears songs about heroes and tells William’s story when she can.

“There’s a lot to his story that people — especially people not from here — are missing, that they’re not privy to,” Tressie said. “He’s a fallen officer, but he was a lot more than a fallen officer. I can’t think of a single person in my life, ever, with so many positive traits.”

The nation will always remember William Durr the deputy. A host of law enforcement officers, a mile-long escort and the governor bore his body to the grave. His name will be on the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial forever.

But there’s another man — a good man, his family says — who needs to be known. He wasn’t just William Durr the cop, but also William Durr the Christian, the husband, the father, the son, the brother, the man who loved to work with wood, play guitar, fish and pull pranks.

The man of God

“He cared about everybody, and always did the right thing,” said Megan Cook, Durr’s sister. “You never had to wonder if he was doing the right thing, because he just always did.”

William was president of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes at Loyd Star Attendance Center, where he graduated in 1998. He was a member of Philadelphia Baptist Church in his youth, where he would say his mother “drugged him to church” every Sunday. He went for a Christian education at Mississippi College, where he first got into ventriloquism, a talent he would use the rest of his life to minister to children.

“His junior year there, instead of asking for a new car for Christmas, he asked for a puppet,” said Debbie Durr, William’s mother. “He had seen some people doing a puppet show, and he wanted to try it. When he was little he had that old Charlie McCarthy puppet, but it was creepy.”

William would take his faith into practice after college, serving as either pastor or youth minister at Concord Baptist Church in McCall Creek and Friendship Baptist Church in McComb. He crossed over denominational lines and served as youth minister for New Hope United Methodist Church.

At the time of his death, William was a member of Moak’s Creek Baptist Church in southern Lincoln County, where he and Tressie taught a college and career Sunday school class and helped run Vacation Bible School every summer.

Later, when William decided to become a law enforcement officer, it was because of his faith, not in spite of it.

His family has heard stories from the people he touched through the badge. He prayed with parents who lost a child in a car wreck. He prayed with a family in the hallway of the hospital before a family member went in for surgery — after they’d gone in and shut the door, they heard him out in the hall, alone, still praying for them. He kept a stash of dolls and stuffed animals in his patrol car to comfort children if he encountered them at accident scenes, or on domestic calls.

He never skipped court. He was always there to testify in cases where he was the arresting officer, not for retribution or revenge, but to make sure those he arrested were held accountable and on the road to correction.

“You did not stand a chance if he wrote that ticket,” Megan said. “He never let people off a DUI. He felt like he needed to protect people, and he needed to protect them, too.”

Tressie said William chose law enforcement because he believed the badge would allow him to connect with more people and share the love of Jesus.

“He was trying to show God’s love to even the weakest of people,” she said. “It didn’t matter to William who you were or what your trouble was — you were a person.”

The joker

It is, unquestionably, the most heinous photograph ever taken.

A man stands before the Eiffel Tower in Paris, a wide smile spreading across his face beneath a thick, black caterpillar mustache. He is on his tiptoes, his rear end pointed toward the camera, and from his too-short, cutoff shorts hangs both his butt cheeks, whiter than Elmer’s glue and covered in curly black hair.

It was a birthday card William got for Megan one year. He insisted she hang it on her refrigerator.

“I had to take it off my fridge because I got tired of seeing that hairy butt every time I went to get food,” Megan said. “At some point he had it made into a magnet and stuck it back on there.”

It was a game they played, William and Megan, to see who could get the other the most terrible gift for birthdays and Christmases. William Durr the comedian was a man his family laughed at, laughed with and, sometimes, just had to endure.

William gave Megan a Hillary Clinton chia pet for her birthday in 2016. She grew it until it molded and still keeps it under the kitchen sink. On a day off, he drove to McComb and filled up a youth group student’s car with packing peanuts — she, in turn, gathered them up and poured them in Tressie’s car.

“He was very friendly, very social,” Tressie said. “He loved to play jokes on people.”

Megan remembers the family’s last Christmas with William, in 2016, when her brother decorated her home, badly. Every strand of lights was a different color. In the yard were seasonal inflatables, collapsed and broken, only half-full of air.

She would try to hide the hideous display by unplugging the Christmas lights. But William worked the night shift for the sheriff’s department, and every night that December he would stop, at some point after dark, and plug the lights back in. Until Megan threw the breaker.

“He called me one night and said, ‘Hey, your lights aren’t working,’” she said. “I said, ‘Yeah, I know.’”

In the middle of the yard was a homemade sign William painted, in red, to say, “Mary Crimas.” William’s mother complained about the sign, so he came back to “fix it” by painting over it and making it even worse. Debbie kept it after his death.

“I pulled that sign out this year and put it in my yard with a spotlight on it,” she said. “Just to have him there.”

The second coming

of William

There’s another William Durr developing. The family says William’s son, 12-year-old Nash Durr, is the image of his father — he looks like William, and he’s just as outgoing, just as sincere, and his sense of humor is already a little twisted.

“Nash gave me a ‘poop emoji’ pillow,” Megan said, rolling her eyes. “Nash is just like him.”

The family has done their best to shield the youngster from grief, to shut the door on their own pain in the hardest times — holidays, anniversaries, milestone events William was a part of, events he should still be a part of. They try to allow Nash to see only the good memories, only the pride they have in his father.

The son says he wants to be a computer engineer when he grows up, or maybe a professional YouTuber. He’s into supercars, like Lamborghinis, the video game “Fortnite” and, like all 12-year-olds, chicken fingers.

After he attended his father’s memorial service in Washington, D.C., earlier this month, Nash was awed by the camaraderie and respect, the uniforms and the choreography and the tradition, the worldwide brotherhood among law enforcement officers.

Now, he says he wants to be a cop.

“I told him, if you feel like that’s what’s going to make you happy, do it,” Tressie said. “I could just be walking down this hallway, and if it’s my time to go, it’s my time to go. Sure, there’s some concerns there, but you have to do what makes you happy. I think he feels like if he did go into law enforcement, that would memorialize his daddy, carry on the legacy.”

Debbie — Nash calls her “Nonna” — isn’t so fearless.

“When he told me, I didn’t say anything. But I would worry,” she said.

The long wait

Everyone agrees — William Durr is in heaven now, and they’ll see him again one day. They’re still working through the rest.

The Durr family functions had to move out of Debbie’s house, where they’d been all William’s and Megan’s lives. It was too familiar, too comfortable, too lacking William. This year, and for the meantime, Thanksgiving and Christmas and all the important family events are held at Megan’s house, which is new and free of spirits.

Debbie no longer gets the same phone call at 5:50 p.m. every evening, a check-in call William made 10 minutes before going on-shift. Megan no longer gets the nightly drive-bys and check-ins from a white and yellow patrol car.

“I would give anything to see blue lights pull up in my driveway again,” she said. “I would give anything for that.”

After William died, Tressie said she couldn’t stay in her and William’s home for a while. She stayed with her parents long enough to get some healing done, and went back to her own house in February. She wants to remodel it one day soon, to convert one room into a memorial room for William and all the reminders she has of him.

For now, Tressie focuses on her work as an optometrist, makes travel plans for her and Nash and leans on the support from her families — her blood family, and her family at the Lincoln County Sheriff’s Department, which she says has blessed her with love.

She says there’s no getting over William’s death. There is only getting through it.

“William, in his selflessness, would not want me moping around. He would want Nash and the community to see me getting through this,” Tressie said. “I put myself in William’s shoes — he would minister to other people, and that’s what I have to do. I can bend an ear. I can listen, I can be there for somebody else. That’s where my strength comes from. If I’m moping around and sad all the time, what kind of witness is that for other people?”